David Foster Wallace once said, “The person I’m highest on right now is George Saunders.”

At twenty-nine years old with no steady income other than the .10 cents a word I get from my freelancing gigs, I am shocked that I am able to afford a better drugdealer than the late David Foster Wallace’s.

Don’t let my bad pun fool you. George Saunders is indeed worthy of a good high. Just this past summer he gave the commencement speech for the Syracuse University class of 2013 where he famously said: “So here’s something I know to be true, although it’s a little corny, and I don’t quite know what to do with it: What I regret most in my life are failures of kindness. Those moments when another human being was there, in front of me, suffering, and I responded…sensibly. Reservedly. Mildly. I’d say as a goal in life, you could do worse than: Try to be kinder.”

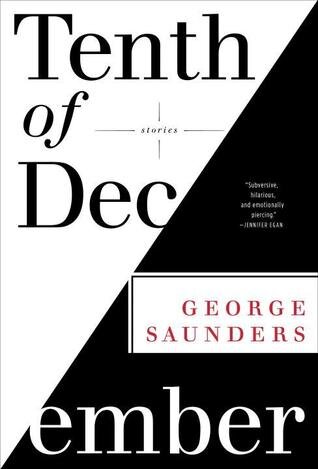

This is true and simple advice that could only be delivered by someone who has a good grasp of his own youth and regrets. Coupled with the fact that he and Wallace’s friendship was as legendary as Laverne & Shirley’s, and that The New York Times in January said that Saunders had written the best book of the year, one would expect a psychedelic level high from reading Saunders’ latest short story collection, Tenth of December. Unfortunately this isn’t the case.

Reading Tenth of December is more like being in 6th grade all over again and scoring your first joint. After lighting it up behind the school’s cafeteria, you’re left wondering, “Is this what all the fuss is about?”

That sounded meaner and way more symbolic than it was meant to (I promise to drop the drug analogy going forward). I’ve been familiar with Saunders’ work ever since the titular essay of the collection published in The New Yorker back in 2011. I liked it, but my opinion of him remains the same two years later: Saunders works best as a gateway for readers who haven’t yet discovered the full terrain of literature that goes beyond the stuffy classics we learned in school.

I would have been wild about this shorty story collection had I read it in high school or even early college. Saunders writes interesting characters that don’t appear often in the literary landscape. I was rooting for his character Jeff in “Escape from Spiderhead” because I felt the weight of injustice being delivered onto the character after he was wrongfully drugged for scientific purposes.

“They shouldn’t be running experiments on Jeff,” I heard my inner teen say as I read through the story. “Fuck the system.”

As an adult, the stories in this collection don’t have the same thematic closure after being spoiled by the likes of David Sedaris and Julio Cortazar. There’s a sense of finality in their works, but with Sanders I’m left bewildered and wanting a bit more of an explanation. I can no longer justify phrases like, “fuck the system,” after reading a story and feel I learned a lesson about injustice. Rather, the pragmatic adult in me needs to know what the system is and why experiments are being run on Jeff before I can make my own conclusions. This may be my own shortcoming as a reader; however, it should be noted that both of the questions I posed were left unanswered by Saunders.

It’s true a good author knows to leave us wanting more, but these stories feel incomplete and are void of context. Context is particularly important for readers because it grounds us and allows us to navigate the story. Take for example “Sticks” where we get the story of a widower who decorates a pole in front of the house. Again, that’s a very interesting premise, but we have no proper background information on the widowers, his wife, or even his children. There are no takeaways other than a vague message about grief and parenting.

It’s not that Saunders’ work isn’t prodigious or marked with precision. He shows readers of Tenth of December a dystopian alternate universe where girls are kidnapped in broad daylight and little boys are chained like dogs in their backyard. And it was believable. The narratives make readers wonder about the wrong turn the American dream has taken in the past few years where a global economic meltdown is possible and the only thing that phases our society are Instagram photos of what we had for dinner. We’re a society of thick skin now and so we need big stories in order spark some kind of emotion.

Saunders also throws some curve balls to the traditional literary archetypes. He delivers to us heroes that are passive rather than active, women who are once more damsels, and villains that are devices meant to provoke thought rather than action. Perhaps the greatest example of this is in “Victory Lap” where an adolescent girl named Alison is kidnapped right in front of her neighbor, Kyle. Kyle wants to rescue her but first weighs the pros and cons of doing so in a protracted inner monologue that can only be delivered by someone born of the Facebook generation. Sadly, the inner turmoil leaves the reader more curious about his home life than the action unfolding before him. Similarly, Alison may be a damsel, but she is not without heavy character history, and her perpetrator’s intentions may not be all that sinister, albeit murky. In the end I wanted to know more about the characters than the actual story.

Good stuff, right? Perhaps the problem is reading all these stories back to back because when anthologized they lack za za zoo. They’re interesting, no doubt, but like I said earlier, there isn’t much closure and we are left struggling to decipher a larger theme of despair and disillusionment in modern America. In “Exhortation” a supervisor named Todd is trying to motivate his employees by using a story about how he and his son were able to lift a whale together. That’s funny and a hyperbole of what happens in the American workplace (who hasn’t gotten a memo like that from their Michael Scott-esque supervisor). There is also mention of a Room 6 where readers infer there are nefarious happenings occurring within. What actually happens in Room 6? Who knows? But Saunders is trying to make commentary on the 2008 market meltdown but fails to deliver the point through a poorly constructed mystery that leaves us wondering more about assassins than a recession.

“The land of the short story,” Saunders once said in an essay, “is a brutal land.” Saunders wanders through this land with brevity and speed. He would be wise to slow down and perhaps look at the map before aimlessly wandering in the wrong direction and passing important landmarks.